| Summary

of Rotation Curves of Galaxies |

The nature of how gravity works has never been understood as regards galaxies. And yet paradoxically, the simplicity of Newton’s inverse of the square law (g=m/r^2) is elegantly precise when considering solar systems. Near the center of a solar system, a body like Mercury will orbit quickest. And yet with spiral galaxies the opposite very often holds true; with outermost stars exhibiting too much velocity. The answer I have programmed by computer algorithm is extraordinarily simple: Spiral

galaxies are binary systems |

|

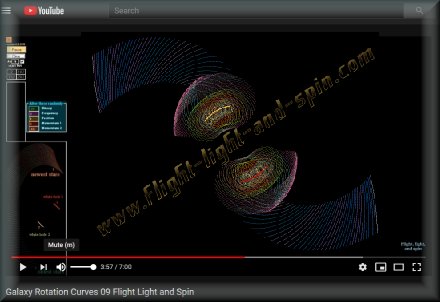

A spiral galaxy consists primarily of two super-massive bodies which orbit each other whilst they also spin on their own individual axes at a phenomenally high velocity. They are so massive and spin so quickly that stars (or pre-solar masses) are thrown out at their respective equators. The newly formed stars then spiral outwards and thus take the shape of the spiral arms of the galaxy. Their peculiar rotation curves are a result of this process without any change to Newton’s law of gravity. This is described in a graphic which was generated in a gravity simulator: |

In a system with a single center of gravity, the orbital body is pulled back inwards, and therefore takes on the shape of a classical orbit. But when there are two centers of gravity, the main body moves away from the smaller orbital body, and so the gravitational force of the main body is greatly diminished. The star then rotates outward, often reaching escape velocity. The next image is a photograph is of spiral galaxy NGC 1365. Compare it to the computer generated image above. It is quite easy to see exactly where the two super massive bodies are situated: |

|

Stars

that fall inbetween the two supermassive bodies are being pulled in

two directions at the same time. Their orbital velocities diminish so

that it is almost nothing at the center. Stars near the center are then

mostly only affected by each others force of gravity. The strong glow

of light at the center is the result of many of these stars colliding

in a terrific explosion! |

|

Click

the link below and Download

|

The

super-massive pair I have termed ‘white-holes’ as they emit

mass and energy. Each star is quite tiny in relation to a white-hole.

During the early period of the universe, the white-holes had more energy

and were closer together. Thus the stars furthest out were thrown out

at the greatest velocity at that time. As the white holes lose mass,

their gravitational force becomes less, so the stars they emit have

less force applied to them, which is why newer inner stars move slower. |

| Stars are not normally in a classical elliptical orbit for three reasons. Firstly, when orbiting a binary pair, the shape of the orbit is never elliptical. Secondly, having been thrown out beyond escape velocity, the stars are not in an orbit, as they spiral outwards. And thirdly, if the main binary pair fluctuates in highly elliptical orbits, this process causes the stars to be emitted at varying velocities. This is why in some cases the rotation curves are said to oscillate. In cases where the white-holes orbits’ are near-circular the velocity of the stars is constant beyond a point. This point is the very position of the white holes. The oscillation in the rotation curves thus represents the period of rotation of the white holes. |

| I arrive at this answer due to having written and observed a software algorithm which uses Newton’s law of gravity exactly as it was first established in the 17th century. Other than the starting spin imparted to the stars and white-holes, the algorithm operates thereafter strictly according to g=m/r^2. As the stars spiral outwards away from the center they eventually die out. They lose their luminosity, but retain much of their mass, and thus can be detected via the phenomenon known as gravitational lensing. The dead stars then become dark matter; which is quite simply matter that does not emit light, but still has gravitational effect. However, not all the stars die like this. Some stars collide at the center of the galaxy. Here, a large amount of light and energy is emitted in ongoing catastrophic collisions. Proportionally there is little mass and thus little velocity at the center. Galaxies near to us appear older. Thus they undergo more such collisions as they have emitted more stars. These collisions then cause more energy to be emitted than in further, younger galaxies. The computer algorithm was only possible due to my having solved the notorious many-body-problem, which entails how to calculate the interactions of numerous gravitational fields simultaneously. I have displayed the graphical results of the software on my website, as well as the solution to the many-body-problem. The algorithm itself can be downloaded and observed in several real-time gravity-simulators like the orbit-game-4.exe application which shows how spiral galaxies form. This is a brief summary of just this one chapter of the thesis. The entire treatise entails several dozen other such answers, many of which were arrived at as a result of the solution to the many-body-problem. I believe my answer to the question of the rotation curves of galaxies is not difficult to comprehend as it leaves Newton’s law of gravity intact. The software makes it easy to observe. |

|

Click

the link below and orbit-game-4-3.exe

demonstrates how the binary pair move away from each other as they lose

mass due to stars having being emitted. Thus stars emitted subsequently

are effected by a lesser gravitational force, moving them more slowly.

The outer and older stars have often reached escape velocity. |

|

The

solution to the many-body-problem: |

| Extract

from the book |

|

< top > < seti > < why? > < credits > < contact > < dark energy > < dark matter > < binary orbits > < the big unwind > < force of gravity > < zeno and planck > < quantum gravity > |